|

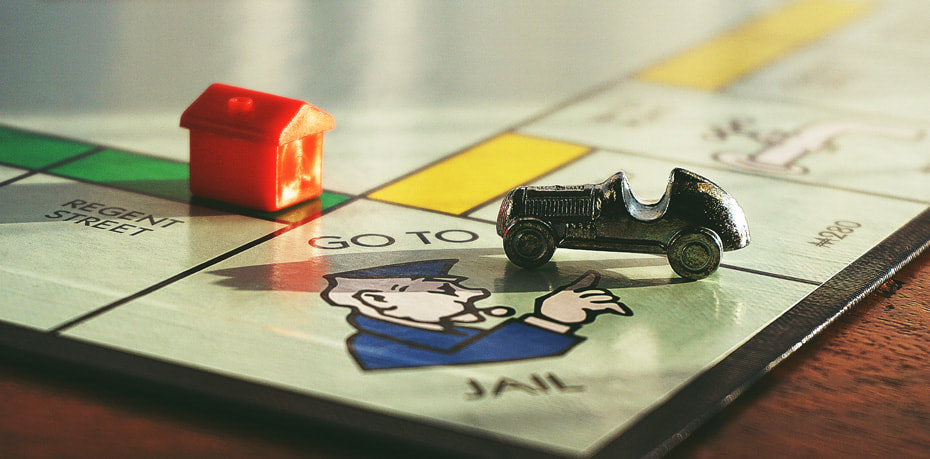

Following a request from the Bank of England, a report was issued last year by a financial markets standards setting body (FMSB) on patterns of misconduct in financial markets. The report analysed 400 cases over more than 200 years. The patterns of misconduct fall into a core group of seven general categories of misbehaviour discussed in this blog. They are constantly repeated. They apply to all asset classes, from US Treasuries to onion futures, and to Bitcoins. The time period analysed by the report corresponds with the rise of democratic politics. This blog looks at how far such patterns of behaviour can be seen in politics. It asks whether we should be sending more politicians to gaol. Misleading customers

In financial markets misleading participants constitutes misconduct. One form of misconduct involves window dressing where actors manipulate prices, or other information, in order to enhance portfolio performance prior to a reporting period. Another form involves ‘spoofing’ where orders are placed with the intention to cancel them prior to their being filled but which give the illusion of market activity. In the case of politics we can think of ‘reporting periods’ as the period of the run-up to an election. Parties have to account to the electorate what they have done, and also say what they plan to do, in order to persuade people to vote for them again. In such political reporting periods ‘window dressing’ is the norm. ‘Spoofing’ where parties make promises they have no intention of fulfilling is probably rare. However, political parties routinely exaggerate their accomplishments and performance in office. They routinely offer guarantees or make promises for the future that will be difficult or impossible to fulfil. Collusion and information sharing Collusion involves pre-arranged transactions organized between two or more market participants that helps them avoid exposure to competitive market forces. It also refers to behaviour that gives a false impression of market activity but enables the participants to close their positions at a profit. One form that collusion may take involves ‘withholding’ where there is agreement not to trade. In politics the analogy to withholding behaviour involves political parties taking important matters of policy ‘off the agenda’. Such behaviour arises when competing parties each have their own reasons to avoid debate. For example, the shape of European political union is divisive for many parties in Europe and so they avoid talking about it. Such behaviour is tacitly collusive, forestalls competition between different party offerings to the electorate, and denies voters choices between alternatives. The risk colluding parties face is that new parties may arise to exploit the gap, such as Afd in Germany and UKIP in the UK. But challengers face an uphill battle to get established and confront the combined antagonism of incumbent parties. Improper order handling In financial markets improper order handling involves conflicts of interest between clients and market participants in the execution and management of client orders. It involves the manipulation of allocations, or the misuse of information about pending orders. In politics, order manipulation can be witnessed when governing parties rank their actual priorities in office in ways that may depart quite radically from the priorities they set out in election campaigns. In some cases changes in the ordering of priorities may reflect a separation of powers. For example, a US President from a party that does not control both Houses of Congress may not be able to deliver according to the priorities set out in campaigning. Even with a majority in both Houses, President Trump was not able to repeal Obamacare. But the behaviour is also common where there is executive discretion and room for manoeuvre. For example, the governments of Italy and the UK have both indicated they are attaching priority to bringing austerity ‘to an end’. In practice, the timing is unclear and other policy issues may claim their prior attention. Inside information In financial markets, abuses arising from insider information occurs when actors have price sensitive information by virtue of their position, or for example, through access to email accounts, that can then be used to their own financial advantage. In democratic politics governments often have privileged access to information not available to others, including to parties in opposition. There is a basic asymmetry of information vis-a-vis the general public. Governments routinely use this information advantage to their own benefit. They may try to supress information that is awkward, embarrassing, or that runs counter to a stated policy, or conversely release favourable information selectively. FOI requests aim to correct for the abuse of insider information. In addition, in the UK, political parties out of office receive briefings from the civil service prior to elections so that they are at less of a disadvantage about what is going on compared with the party in government. Nevertheless, governments usually are at an advantage in the information at their disposal and routinely exploit that advantage. Circular trading Circular trading involves ‘matched’ trades that do not involve changes in ownership or transfers of risk. They are spurious trades that can be used to manipulate the price of a stock, or to give false impressions about prices and market volume. A variant involves engaging in transactions that are undertaken to compensate for some form of other service. In politics, compensatory behaviour is widespread. It takes place whenever there is coalition government, or when bargaining takes place between different centres of power. It is typically referred to as ‘horse trading’ or ’log rolling’. It involves one party to the bargain giving up something to the other party in exchange for something they want. They are matched in the sense that each party sees their loss cancelled out by a compensating gain. In financial markets spurious trading is against the public interest. In the case of politics, the trades may be genuine. Log rolling does not necessarily work against the public interest. However, deals are not always transparent and may be misrepresented. Price manipulation In the popular imagination, price manipulation is associated with attempts to ‘corner’ or ‘squeeze’ a market, where a market participant attempts to achieve a dominant or controlling position in a commodity or security. There is a long history of such attempts from the very first issue of US Treasury bonds in 1792. Price manipulation can also take the form of spreading rumours or false information about an asset in order to benefit the position of the publisher of the rumour. Again there is a long history of such behaviour. In today’s world, rumour spreading has readily adapted itself to the world of social media. The social media also allow actors to disguise their identity. In politics, the analgous behaviour involves attempt to manipulate public opinion through the spreading of ‘false’ news, or by attempting to discredit what may be genuine news by labelling it ‘fake’ news. Again the social media plays a prominent role. Again, identities may be disguised. Facebook, Google & Twitter have all adopted measures in recent months to improve transparency applying to political advertisers. However, this still leaves open a vast swathe of social media for rumour spreading from unverified sources. The issue for democratic politics centers on the authenticity of news and the separation of authenticated facts from opinion about the facts. The traditional media had an incentive to authenticate what they spread because they wished to build and market a reputation for reliability. Their decline allows much greater space for the unauthenticated. In theory, politicians also have a strong self interest in being seen as reliable and honest. However, the imagery of politics can be shaped in many different ways in order to convey what the candidate or party stands for. Even where the image being projected is intended to stand for honesty, for example in President Trump’s self-depiction as an ‘outsider’ ready to ‘drain the swamp’, it may be misleading. Reference Price influence Reference prices in financial markets are prices against which positions are valued, such as a closing price. Misconduct arises where there are attempts to alter prices at the valuation points to the benefit of the perpetrator. In politics, references prices are provided by public opinion polls. Politicians are engaged in never ending attempts to influence them. They anticipate and mimic them through focus groups and conduct their own polling. The justification of such behaviour in politics is that it enables political parties to keep in touch with public opinion and to adjust and to shape party programs and policies in response to public opinion. Far from being against the public interest, it is supportive of democratic politics. It is difficult to imagine contemporary democratic politics without public opinion polls and generally their effect is seen as benign. The plea bargaining of politics In cases of allegations about financial misconduct, the parties to the case often settle without the expense and uncertain outcome of going to court. Defendants may be able to avoid any admission of wrongdoing in plea bargaining. There are four main reasons why politicians engaging in analogous behaviour, could also engage in plea bargaining, deny wrongdoing and expect to settle charges of misconduct. The first is about intent. Politicians claim that they do not campaign with the intent to mislead or defraud. They claim to engage in politics with an idea of the public interest at heart. Secondly, the language of politics is often imprecise and ambiguous for reasons that are seen to be ‘good’ reasons. For example, a degree of ambiguity allows a candidate for office to appeal to a wider audience and to avoid pandering to extremes. Thirdly, there is a widely accepted latitude around the role of an elected representative. At one end, some politicians see their role as representing what their constituents voted for and trying to do what they said they would do. At the other end, other politicians see their representative role as permitting substantial discretion to act in whatever they themselves consider to be in the best interest of their constituents. They therefore claim the latitude to amend or contradict whatever they said in the process of getting elected. Finally, politicians tend to face a lot of unknowns in trying to implement their promises. The ability of financial markets to give concrete commitments to execute promises on agreed terms and to achieve best execution is usually missing in politics. Politicians are often unaware of the full circumstances they will face in trying to fulfil their promises. On the whole, democratic systems accept these pleas. Politicians who fail to execute their promises, who engage in misleading rhetoric, spread rumours and make undeliverable promises, do not go to gaol. At the same time, there still needs to be some form of retribution. The retribution of politics The main form of punishment meted out to politicians who engage in behaviour that in other circumstances would amount to misconduct, is that voters can turn to vote against them. Negative voting is widespread and powerful in democratic politics. By contrast, non-democratic countries do not allow negative voting opportunities. They operate on the opposite basis of giving rewards to followers. Another form of retribution in democratic countries is that in some jurisdictions, and in some countries such as the UK, constituents can vote to recall a politician. The need to be reselected by a constituency might achieve a similar purpose of keeping politicians to their word. The problem with both recall and reselection procedures is that they can deliver power to party extremes. A further technique, which does not depend either on electorates, or constituents, is provided by term limits. Some people might consider that when an elected politician has spent two terms, or eight or ten years, engaged in making imprecise and ambiguous pledges, shuffling priorities, and under-the-table horse trading, that ‘enough is enough’. Term limitations In practice, politicians require a large margin of allowable discretion in what they actually do in office. However, currently democracies are struggling. People do not trust politicians. They appear less deferential towards those in authority than in the past and wanting a more directly responsive style of politics. Perhaps, therefore it is time to take a less forgiving and lenient attitude towards behaviour in politics that followed elsewhere would land you in gaol. President Trump’s followers chanted ‘lock her up’ targeted at Hilary Clinton. The analogies in this blog suggest that misconduct lies more with President Trump’s manipulation, misrepresentations and misuse of the social media. Perhaps we need to give a much larger place to term limitations. It would take away some of the incentives for politicians to economize with the truth. It would discourage those seeking a lifetime in politics. It would bring in those with experience of different standards from different walks of life. It is unfortunate that President Trump seems to have imported lower standards. Even he will not get a third term and maybe not even a second.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed