|

This blog looks at the idea of the ‘Anglosphere’. The most recent use of the term has come in the context of the Sept 2021 AUKUS security agreement on nuclear submarine, AI and other technologies, between Australia, the UK and the US. The Anglosphere is a term without a clear and fixed definition and with many ambiguities around the use of the term. This blog looks at the different components of what might be conveyed by its use. Origins: Alliance theory

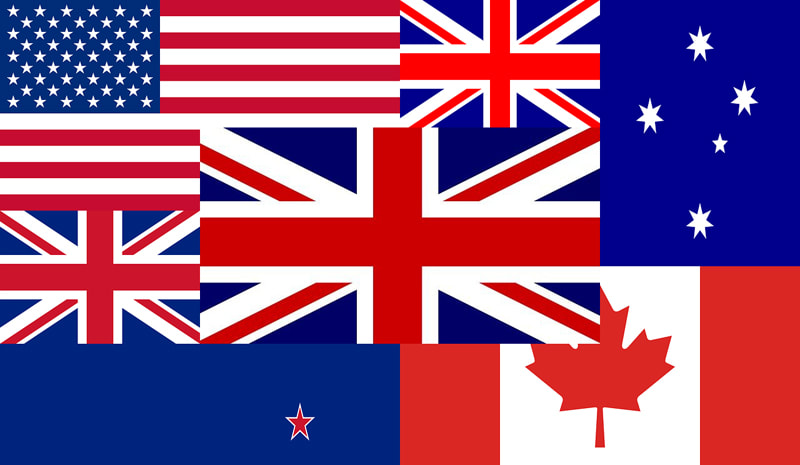

The origins of the concept of the Anglosphere can be traced back to the end of the 19th century. One of the most important early proponents was Alfred Milner and his band of surrounding acolytes, known as the kindergarten, including John Buchan (see post of 3/1/2019). Milner had experience as a British colonial administrator in Egypt before becoming High Commissioner in South Africa between 1897-1905. His aim of ‘anglicisation’ is held responsible in large measure for the Boer War. During the First World War he was a member of Lloyd George’s War Cabinet. Milner’s belief in the superiority of the British and their civilising mission in the form of Empire now appears highly outmoded and mistaken. The racist component of his thinking is repellent. But he was unusual in taking a long-term geopolitical perspective. He recognised the end of Britain’s role as the predominant global power, and he looked to see how the benefits of Pax Britannica could be maintained in the world in the face of the relative decline of Britain itself. His answer was to turn to the former colonies that had attained their own sense of nationhood within a democratic framework, and specifically to Canada, Australia and the United States. He wanted them to act together alongside the UK to defend a shared conception of world order. An illusion? Today the idea of the Anglosphere can be immediately criticised as reflecting a misplaced nostalgy in the UK for an imperial past and as representing no more than a forlorn attempt to salvage something from the wreckage of BREXIT. The AUKUS security agreement led to an immediate row with France over the cancellation of a submarine purchase agreement with Australia. Nevertheless, if the idea of the Anglosphere has traction, it is for reasons other than nostalgy and a salvage operation. If the Anglosphere has a place in the world today it is because there is still a continuing need for concepts that can help to manage shifts in great power relationships. Some shifts in relative power are benign, such as the rise of India and the growth in the importance of the EU. Others are not. A risk reassessment of Russia is taking place in the light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and risks are also being reassessed in transactions and relationships with the rising power of China. An era of unreflecting engagement between countries that are broadly democratic and those that are autocratic, that prevailed at the end of the 20th century through the first two decades of the 21st century, is now over. There is an overdue move among democratic powers in the direction of a much more conditional engagement with autocratic powers. A new struggle to position the values held in democracies relative to the values espoused by autocracies is underway. Who is included? The appeal of the Anglosphere can be viewed as belonging to the search for new defensive realignments and new patterns of engagement in this much more challenging environment. The countries of the Anglosphere practice different forms of democracy. Nevertheless, they share a desire to protect their territory and to protect their version of a democratic way of life. In different ways they uphold a conception of the rule of law where law is not simply the instrument of those in power but has a legitimate purpose in constraining the arbitrary exercise of government power. Membership in the Anglosphere is flexible and is defined by regional challenges as well as global. In the global context, the 5 Eyes intelligence sharing between the US, UK, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand defines a core membership. But in regional constellations the core may differ, as in the case of AUKUS. Typically, it is the US that is the convenor rather than the UK. Regional constellations convened under Anglosphere leadership may also include members lacking any history of British colonisation, as in the case of the Quad bringing together Japan along with the US, Australia and India. As the old Cold War and post-colonial appeal of ‘non-alignment’ fades and other groupings such as the BRICS lose relevance, the Anglosphere may also gain appeal in Africa and other parts of the post-colonial world where democracy has a hold and needs to be defended. Nigeria’s 2018 Security and Defence partnership with the UK may be a sign of the future. A shared motivation to come together for defensive reasons does not necessarily provide the ‘glue’ needed to hold together alliances. In looking for the underlying ‘glue’ of the different formations of the Anglosphere, there is a highly deceptive cultural terrain of ethnicity, history and language that enters the frame. Ethnicity Alfred Milner referred to his version of the Anglosphere as ‘Family’. In his conception, a founding ethnicity of English, Scots and Irish provided a family underpinning. In today’s world any such ethnic claims must be put aside. Each of the countries in the Anglosphere recognise the importance within their societies of their intercultural mix and mingling. The shared British component of history also must be viewed with caution to recognise the very different perspective of the colonised compared with the colonisers. Even the shared use of English as a common language must be viewed as a heritage with a downside as well as an upside. On the one hand English is a global language and in countries with linguistic diversity it can provide an important common linguistic tie. On the other hand, in Asia and Africa, it also defines the political elite and can be a marker of social and income divisions. Thus, neither ethnicity, nor history, nor language provide any straightforward or unambiguous ties or cultural ‘glue’. Trust Among the intangibles that bring and hold together the Anglosphere probably the most important is trust. Trust is possible where there exists a history of repeated interactions between the partners and a sense among the partners that the interactions have, overall, been positive. Trust can be said to exist between partners when relationships do not have to rely on formal mechanisms for the enforcement of contracts or for oversight. Information can be exchanged between partners with confidence and the uncertainties attached to information will be shared. The member states of the EU share a common purpose in pursuing ‘ever closer union’. But because they have to overcome a bitter history of mistrust and conflict, the procedures and institutions involve a high degree of third-party oversight, procedural, bureaucratic and legislative formality. The EU is based on the need to overcome historic mistrust; the Anglosphere is based on historically rooted trust. Conclusions The term ‘Anglosphere’ should not be written off as misplaced nostalgia. It has meaning in denoting fluid groupings of countries, mobilised by the US, who share a high degree of trust enabling them to come together for global and regional defensive purposes. These purposes have been enhanced in the new Cold War era where democratic countries have to position their own values protectively in relation to autocratic values in the world including those of a rising power such as China. What remains unclear is how far they will look to expand their cooperation into non-defence related fields such as health and the environment and how far we can expect new regional formations.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed