|

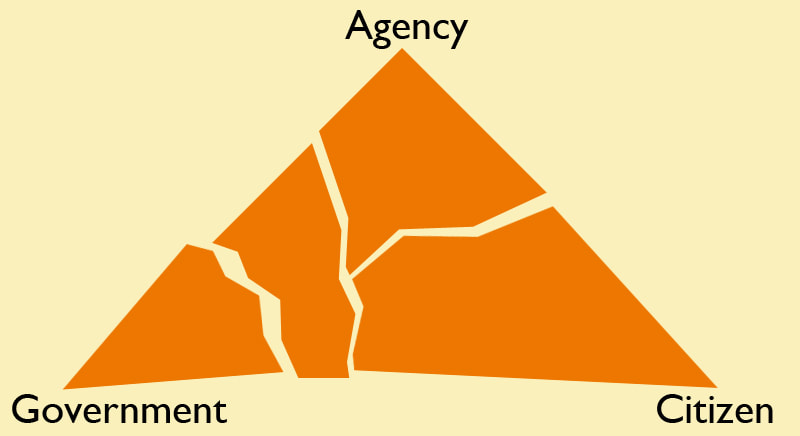

President Trump continues to criticise the US Federal Reserve. A previous blog post discussed how unelected bodies exercising authority in democratic societies should be seen as answerable to more than one source for their legitimacy – to the law, to the standards of their profession, to politicians, to stakeholders and to citizens. Moreover, they are answerable in different ways. That previous discussion left open whether the positioning of unelected bodies can be summarised in way that further clarifies their relationship to democratic norms. This blog looks at the three leading ways in which the relationship is sometimes expressed – as agents, as trustees, or as stewards. Each can be misleading. Most democracies around the world are representative democracies where elected representatives make public policy choices on behalf of the voters. The question is how far the concepts of agency, trusteeship and stewardship help us see how unelected bodies fit within ideas about representative democracy. Agency An agent is a person or body that receives their instructions from a principal. They are told what to do and how to do it. The principal is actively involved in supervising the agent and how they carry out their duties. The trustee A principal can also set up a trust to carry out their wishes. However in this case the trustees administering the trust act independently of the principal and act instead according to the terms of the trust. The link with the principal is deliberately broken. Once the trustee role has been conferred, the principal typically has no further role in how the task is done. The steward The idea of stewardship stands between these two other concepts. The steward takes the place and acts on behalf of a principal. At the same time, the steward remains under the eye of the principal. Unlike the trustee role, the link with the principal is not broken. Unlike the agent role, the steward has very wide discretion and latitude. Stewardship requires discretion and latitude because the steward usually has to be able bring together and take care of all the different relationships and tasks on behalf of the principal. The relationship with democracy In principle, each of these roles is consistent with ideas about representative democracy. They apply, for example, to the role of elected representatives themselves. Some elected representative see themselves as agents of their electorate with their role tightly defined by conforming to what their particular electorate or constituency wants. Others see themselves with the freedom to act in whatever way they themselves consider to be in the best interests of their electorate, thus acting in a manner more consistent with the role of trustee. Yet others see themselves as acting with discretion as long as it is broadly consistent with their party platform (a stewardship role). Thus, in the UK parliamentary debates on Brexit, some MPs have voted strictly according to the wishes of their constituents, some cited ‘the national interest’ as a way of defining what they considered to be in the best interests of their electorate, and others looked for a party line to follow as a guide to allowable discretion. Nevertheless, the concepts do not fit quite so easily in relation to the role of unelected bodies. Agency and representation WithIn a broad meaning of the term ‘agent’, unelected bodies with authority often claim to act as agent of the public or the government. They often are mandated to ‘represent’ a specific public interest in what they do and can be seen to act as ‘agent’ in executing that role on behalf. For example, in carrying out their responsibilities, economic regulators have a specific role in representing the voice and interest of the consumer. They may have even more precisely defined roles in protecting vulnerable groups of consumers, such as the low income or elderly. Nevertheless, unelected bodies are not simply agents of either citizens or elected governments. First, the terms of reference of unelected bodies usually allow them to be able to exercise discretionary judgement. Otherwise terms of reference would be impossibly detailed. Secondly, because unelected bodies have to answer to different sources for their authority, including the standards of their profession, they develop their own standing and authority in how to interpret their terms of reference. Thirdly, the long and dispersed chains of intermediaries typically needed to deliver public policy, also means that there are many different relationships involved between the various actors in the delivery chain. There was a time when the idea of an agency relationship between government, the electorate and an unelected body was shown in the form of a simple triangle with the unelected body at the apex. The reality is that the world of the unelected is a world with few straight lines, or singular points of contact. Trusteeship and representation

Unelected bodies typically enjoy and make use of an arm’s length relationships with governments and electorates. They have considerable influence in framing policy and not just in carrying out policy. Some may act with considerable discretion on behalf of a general public interest. For example, a medicines licencing agency acts with discretion in the general public interest in making its assessment of the risks of any novel medicine or treatment in relation to the benefits. They might claim a trustee role. Nevertheless, trusteeship does not describe the relationship either. Unelected bodies still face limits on the degree of discretion they can make use of. They are not free from outside review and interventions about how they use their authority, particularly if they are seen to perform poorly. The principal still stands ready and able to intervene. Stewardship & representation. In many ways it is the concept of stewardship that appears to capture best the relationship between democratic organisation and unelected bodies. It expresses the task of dealing with multiple relationships. It also expresses the idea of the body exercising considerable discretion. At the same time, the principal remains in the frame. Nevertheless we should also be cautious in applying the concept of stewardship to unelected bodies. It seems to imply that the body is in a superior position to discern the public interest and to make judgments on behalf of all. It seems to imply a higher, benevolent wisdom and authority. The unelected body may indeed be better placed to mobilize and deploy expert knowledge and information relevant to a matter of public policy. The answers it gives in its area of public policy may satisfy fellow professionals and the law. But what still counts is whether, or not, a policy and its implementation is acceptable to public opinion. The most expert analysis of risks, or costs, versus benefits may still be set aside after following all necessary legal procedures because it fails a test of public acceptability. For example, experts may show that fracking poses a minimal risk of damage to the environment. Public opinion may disagree. In turn, what is, or is not, publically acceptable enters the realm of political contestation. This is a sphere where unelected bodies are at a disadvantage. They are not fitted to mediating between contending public attitudes towards a given evidence base. Conclusion: A negative space Unelected bodies are often called ‘agencies’. It may suit their purposes to be seen as mere agents. But that conceals the considerable discretion and authority of their own that they possess in practice. At the same time they are not trustees. They cannot cut themselves off from the interventions of others in how they carry out their duties. Even the concept of stewardship that expresses some middle ground between agency and trusteeship has to be treated with reservations. Unelected bodies have no special superiority in assessing and mediating contending public attitudes towards the evidence. President Trump exploits this lack of a single convenient term to describe their role and would like to see the Federal Reserve acting simply as his agent. Instead of exploiting the ambiguities we should accept that there is no single term of convenience to describe the role of unelected bodies in a way that makes clear how they fit within a democratic system of government. Unelected bodies occupy their own special place defined by a negative reality. They are compartmentalised in order for democratic societies to be able to mobilize knowledge, expertise and information. Theirs is not a task that can be performed by electorates or civil society directly. Nor can it be left to elected politicians. It also involves expertise and relationships beyond that available to the law. They are there because of what other branches cannot do. . Artists would visualize unelected bodies filling a negative space between other actors in a picture of contemporary government.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed