|

Photo by Timon Studler on Unsplash In her novel Romola (1863) George Eliot (Mary Anne Evans) depicts four kinds of ethical behaviour: the reasoned, the self-interested, the emotive and the instinctual. They represent styles we can still recognize today. In today’s diversified and divided societies we face a problem in trying to reach a consensus on all public policy choices where values are important. George Eliot’s four models of the way different people approach ethical questions illustrate the problems involved in trying to find a pathway through our differences. The application of this model to today's world suggests that President Trump will likely not be re-elected. The Pathways through our differences We have three choices in finding a path through differences in social values:

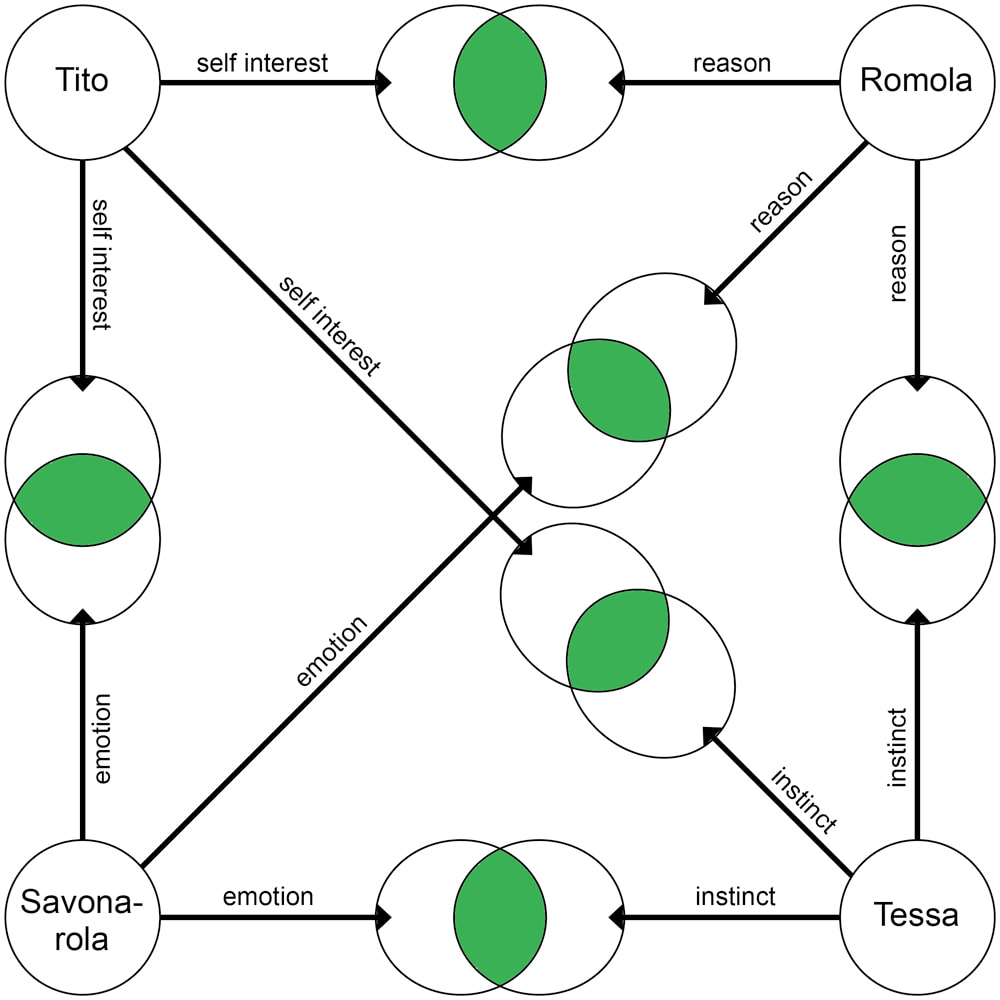

The last option seems weak. It appears to undervalue what is really important to us. It may involve settling for second best, or putting something important to us in abeyance. However, looking for a transitional ‘better there’ can also be seen as placing a high value on the process of social learning. The learning process is unlikely to resolve our underlying differences. But it might lead us towards some temporary mutually agreed choices that are better than accepting the status quo. The setting of Romola George Eliot sets her novel in late 15thcentury Florence around the time of the ‘bonfire of the vanities’. When the novel opens, the Medici are in power. Savonarola is preaching his incendiary sermons against corruption in the Church and against the pursuit of wealth in Florentine banking and commerce. The Medici flee and Savonarola and his followers essentially take over. Public opinion and the papacy then turn against Savonarola. He is publically executed. Traditional order is restored. The models of behaviour Against this background, George Eliot sets out four models of ethical behaviour. The heroine, Romola. She arrives at her ethical precepts through observation, contemplation and reasoning .She has a strong sense of family and social ties. Her suitor and husband (Tito). He is an adventurer and opportunist, driven by self-interest in his own advance. He pays lip service to social precepts that help him on his way. He ignores social obligations. The monk Savonarola. He embraces absolute standards of right and wrong. His oratory appeals to emotion, to Heaven and Hell. The peasant girl Tessa. She is motivated by instinct and trust in those she encounters. She is duped into a sham marriage by Tito and bears his children. A reasoned consensus? In political science there has been an influential view that we might find some kind of reasoned consensus on societal values that enables us to overcome our differences. We reflect, reason and deliberate with others in order to find areas where our values overlap or can come together in ‘equilibrium’. It is an attractive idea from a normative perspective. We would all like to think that we ourselves respond to reason. We would all like others to agree that what are good reasons for us are also good reasons for them. George Eliot’s different models provides a test for how easy or difficult it will be for people with different approaches to ethical questions to arrive at such a deliberative consensus or ‘reflective equilibrium’. We can assess the likelihood by examining their one-to-one relationships with each other and then, the interchanges between the four as a group. The interchanges are illustrated in the chart later in this blog. Agreement With Each Other Romola is open to agreement with each through reasoned persuasion and observation. At first, Tito gives her reasons for trust. She thinks they have common ground. Accord with the peasant girl happens when Romola observes her essential goodness and openness. Accord with Savonarola arrives when his appeal to her emotions overrides Romola’s own considered style of reasoning. The husband Tito can agree with each of the others whenever the values they put forward happen to align with his self-interest. Because his positioning is opportunistic, it is deceitful. Savonarola agrees with each of the others whenever they fall into line with his assertions. He wants dominance and ascendency. He persuades though the power of his emotional appeals, not through debate. The peasant girl Tessa can go along with each of the others by relying on her instinct and willingness to trust others. She is gullible and vulnerable to manipulation. Agreement as a Group If, in order to assess the possibility of a general consensus, we put each of these possibilities of bilateral accord together, then we find the following: A consensus is possible only if Savonarola’s appeals to the emotions are able to displace Romola’s prior reasoning, happen to align with Tito’s opportunistic self-interest, and with Tessa’s instinctive trust. In addition, Romola’s reasoning and Tito’s self-interest must coincide. So too must Tito’s self-interest align with Tessa’s instinct for what is right, or with her gullibility. Tessa’s instinct must also go along with Romola’s reasoned position. If we assign a 50:50 chance to each pair agreeing bilaterally, and if we assume that their approaches are independent of each other, the chances of their all agreeing together can be calculated at between 1% - 2%. If they have only a 1:4 chance of agreeing bilaterally, then the chances of consensus fall to less than 0.1%. The novel reflects this unlikelihood of agreement. Positions are aligned (fleetingly) only at the moment when both Tessa and Romola are deceived by Tito and carried away by the emotional appeal of Savonarola. Imposition? George Eliot’s attributes the turmoil of late 15th century Florence to the disarray produced by the conflict between these four models of reasoned, emotional, self-interested and instinctive approaches to ethical questions. It produced what she refers to as an irreconcilable ‘web of inconsistencies’. We can recognise in modern polarised societies the same four models of behaviour, and the same ‘web of inconsistencies’ between values in our societies. We are likely to face similar difficulties in reaching consensus. We face similar instability. One way to try to overcome the difficulties, and yet to achieve an overall consistency, is for societies to establish pre-set values. These are usually expressed as ‘rights’. They rest on prior considerations that refer to the ‘fundamentals’ of human nature, or of the law, or to assumptions about the ‘pre-suppositions’ that bring people together in political association. Rights enforce these pre-set values because they have ‘injunctive’ power. This means that those with authority are meant to see that they are adopted and respected. According to the models of behaviour in Romola, the assertion of rights will inevitably involve imposition. Their interpretation may not align either with Romola’s reasoning, her husband’s self-interest, Savonarola’s moral absolutes, or with Tessa’s instincts. Thus, in the novel, Savonarola’s imposition of his own evaluation of what is right leads to reaction. In turn, the re-imposition of traditional values results in the execution of Savaranola, the attempted flight of Romola’s husband, while Romola throws a protective shield over Tessa. A learning process Generally speaking we do not want democratic societies to live with imposed values. Democracy is about voluntary association. The alternative is to accept that we live in a situation where people take different approaches to value judgements and that we should look to the procedures for democratic exchange as aids to a social learning process. In an unstable and inconsistent world we do not resolve our underlying differences. But we can at least try to find the step that we can all agree represents a temporary ‘better there’. We accept instability as part of the learning process and do not expect or seek more than a transitory ‘equilibrium’. In Romola the heroine learns from her personal experiences and from the social upheavals she sees around her. She learns to empathize with the peasant girl, to distinguish between the religious message of Savonarola and his secular ambitions to lead a puritan state, and to recognize the duplicity of her husband. She learns that she must provide for Tessa and her children. The Trump Game We can add a contemporary realism to George Elliot’s recreated 15th century world by visualizing the different ethical approaches in chart form and by substituting characters. In the substitution Tito becomes President Trump, Savanarola becomes the evangelical right, Romola continues to stand for the voice of reason and Tessa represents the average, non-urban voter relying on instinct and trust in their own social network. In this world Trump can win the game if he persuades Romola there is reason behind some of his positions (for example that the problems of blue collar workers need to be addressed) if he gains the emotional support of the evangelical right, and can manipulate the average voter (for example into thinking that he is the anti-establishment candidate). At the same time the average voter and the reasoned voter are aligned behind the needs of the blue collar population. In addition, the average voter and the evangelical voter are aligned by a shared distaste for insider, Washington DC, elites. The game suggests that Trump’s winning position will be short lived. The reasoned voter will be put off by the lack of content behind his promises and the evangelical voter will be turned away by Trump’s ethical duplicity. The average voter will realize that Trump’s self-described ‘anti-elitism’ is manipulative. He is not out for them. He is only out for himself. The other side of this message is that challengers to Trump cannot rely on the force of reason alone. They must also appeal to self-interested voters, to those who vote emotively and to those who vote instinctively alongside their associates. Varieties of ethical behavior Institutional Aids to learning

The lessons of all this are:

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed